Restoring from Above: Monitoring Restoration of Fragmented Landscapes

|

With population growth and increased prosperity driving urban and agricultural expansion in the 21st century, the conversion of natural habitat to human-dominated land-uses is expected to accelerate.

However natural habitat is rarely fully eradicated from a landscape. Fragmented remnants are left behind, embedded in a sea of agricultural and urban land. Although extensive ecological research has demonstrated that habitat fragmentation decreases ecological diversity and functioning, habitat fragments are often the last harbors of biodiversity and ecosystem services in a landscape. Viewed in this light, they represent potential foci for the restoration of the natural landscape. The research of the EFA lab focuses on how we can best conserve and reconnect isolated habitat fragments. To do this, we try to understand the process of fragmentation and habitat loss from several different perspectives: ecological, geographical, and socioeconomic. Recent projects have focused on mapping tree plantations (Fagan et al. 2015, 2018, 2022), tracking the recovery of secondary forests (Reid et al. 2019), assessing the impacts of tropical forest fragmentation (Fagan et al. 2016, Rasmussen et al. 2019), and examining the feasibility of global forest restoration maps (Fagan, 2020) and commitments (Fagan et al., 2020). |

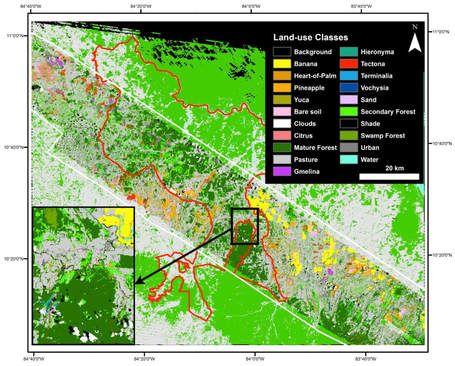

Figure from Fagan et al. 2015. Shown here is a map of tree plantations in northeast Costa Rica, derived from analysis of hyperspectral imagery.

|

Conserving from Above: Assessing Conservation in Fragmented Tropical Landscapes

|

One focus of our research is testing how well conservation initiatives have worked in reducing tropical deforestation and maintaining habitat connectivity. For example, Costa Rica has an international reputation for its commitment to conservation. In terms of governance and economic well-being, Costa Rica could be considered a "best-case" scenario for developing countries in the tropics. By learning from its successes and failures, we can make recommendations to other countries that are following in its footsteps.

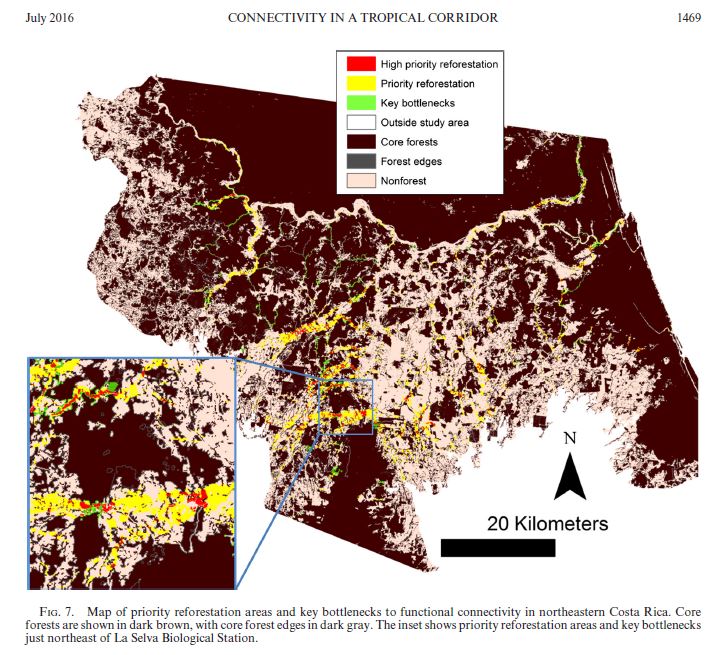

The figure to the right shows recommended areas for reforestation in the San Juan-La Selva Biological Corridor in northeastern Costa Rica (Fagan et al. 2016). Daniel Cunningham, a recent masters student in the lab, expanded our understanding of the effectiveness of the Biological Corridor program across all of Costa Rica. His thesis examined a key tool for that job--the Hansen global tree cover map--and found severe biases in it (Cunningham et al. 2019) that can be corrected, markedly improving estimates of forest cover and fragmentation (Cunningham et al. 2020). Since 2020, the EFA lab has been expanding its work on conservation to other countries, including recent NSF-funded work in the Caribbean (Antalffy et al. 2021, Rowley et al. 2021) and forthcoming work in central America, Peru, and India. |

Ecology from Above: Examining forest ecology in three dimensions

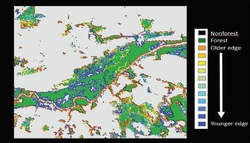

The advent of active remote sensing approaches like SAR and LiDAR have permitted detailed, high-resolution characterization of forest structure. The EFA lab is actively engaged in connecting this data to ecological theories of forest function and growth. For example, when forests become fragmented, it is well known that the presence of edges alters the functioning and diversity of the forest. However, we still don't have a predictive understanding of how and why the strength and penetration of edge effects varies across a landscape.

The lab is currently examining the impact of forest growth and fragmentation on forest structure in a highly productive region, the timberlands of the southeastern US (Fagan et al. 2018, Gopalakrishnan et al. 2019). We are also initiating projects to understand riparian (riverine) forest structure and function in both Maryland and Costa Rica. Both of these landscapes are highly connected by degraded remnant riparian forests, and better understanding the nature and extent of that degradation is critical to maintaining and restoring connectivity for wildlife.

The lab is currently examining the impact of forest growth and fragmentation on forest structure in a highly productive region, the timberlands of the southeastern US (Fagan et al. 2018, Gopalakrishnan et al. 2019). We are also initiating projects to understand riparian (riverine) forest structure and function in both Maryland and Costa Rica. Both of these landscapes are highly connected by degraded remnant riparian forests, and better understanding the nature and extent of that degradation is critical to maintaining and restoring connectivity for wildlife.

Proudly powered by Weebly